Electric Vehicles and Critical Raw Material Supplies

The success of the energy transition depends on reliable access to critical raw materials. That access is also becoming a key national economic security consideration. As geopolitical tensions mount and international cooperation is replaced by economic and political nationalism, competition for these scarce resources is only going to intensify. That competition will be exacerbated by the fact that more than half of energy-related minerals are subject to some form of export controls, which are increasing in number and expanding in scope. To further complicate matters, the most vital raw minerals and metals are highly geographically concentrated and the capacity to process them even more so. This combination of factors carries severe risks for energy transition companies whose success relies on uninterrupted supplies of raw and processed materials.

This is particularly the case for electric vehicles (EV) – whose success is so crucial to the energy transition. According to the IEA, in 2024, EVs displaced over 1.3 mb/d of oil in 2024 (equivalent to Japan’s entire transport sector oil demand), rising to 5 mb/d in 2030. In 2024, EVs globally consumed around 180 TWh of electricity (more than the annual electricity consumption of Argentina).

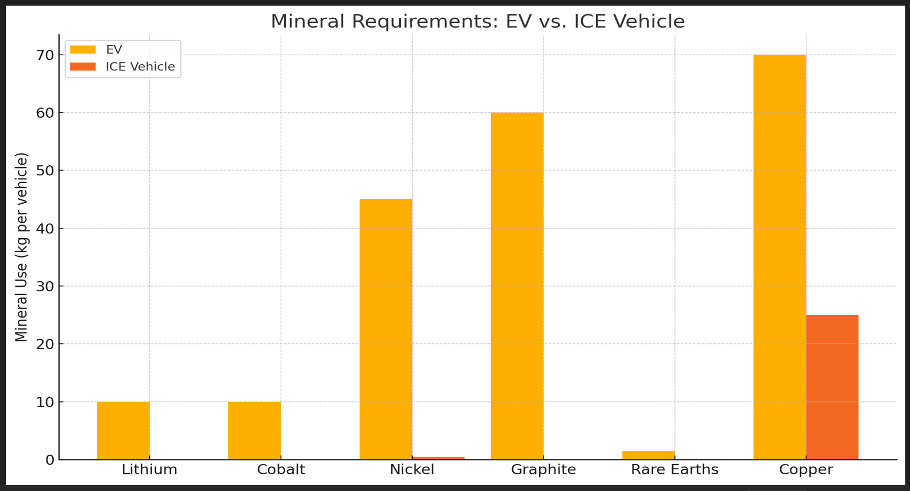

But without access to reliable supplies of rare earth metals and minerals, the EV revolution will grind to a halt. And EVs require significantly higher quantities of rare earths and minerals than ICE vehicles.

According to the IEA, between 2024-2040, the deployment of EV batteries, together with the necessary construction of the supporting electricity grid, will drive a fivefold increase in lithium demand; a doubling in demand for graphite and nickel; a 50-60% increase in demand for cobalt; and a 30% increase in demand for copper. Meeting this demand will require around USD 500 billion in new capital investment in mining between now and 2040. This demand signal has already seen a significant increase in production, which has had a knock-on impact on prices, with lithium falling by over 80% since 2023 and graphite, cobalt and nickel prices falling by between 10 - 20% in 2024.

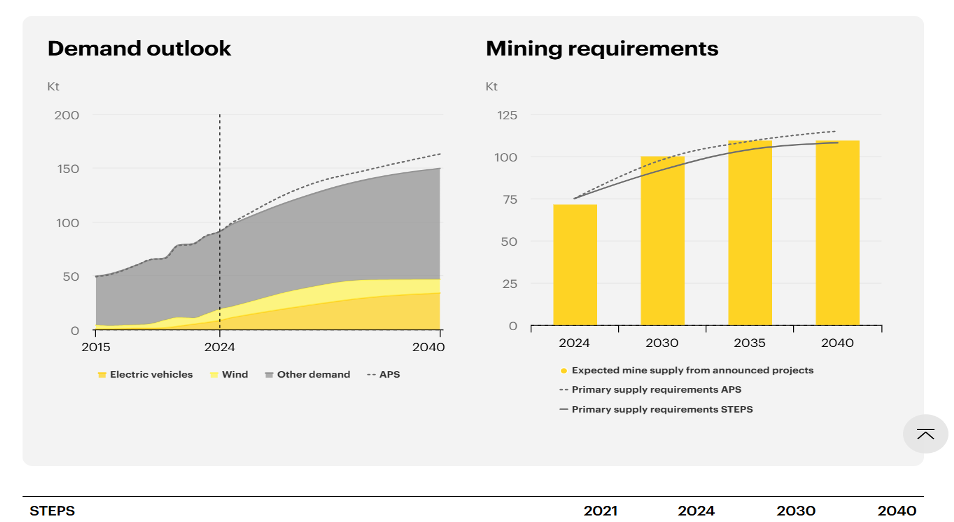

These price decreases are not providing the right price signal to incentivise longer-term investment (lithium mines take an average of 16.5 years to develop) and discourage new market entrants. The IEA’s projections show serious gaps between demand and supply by 2040.

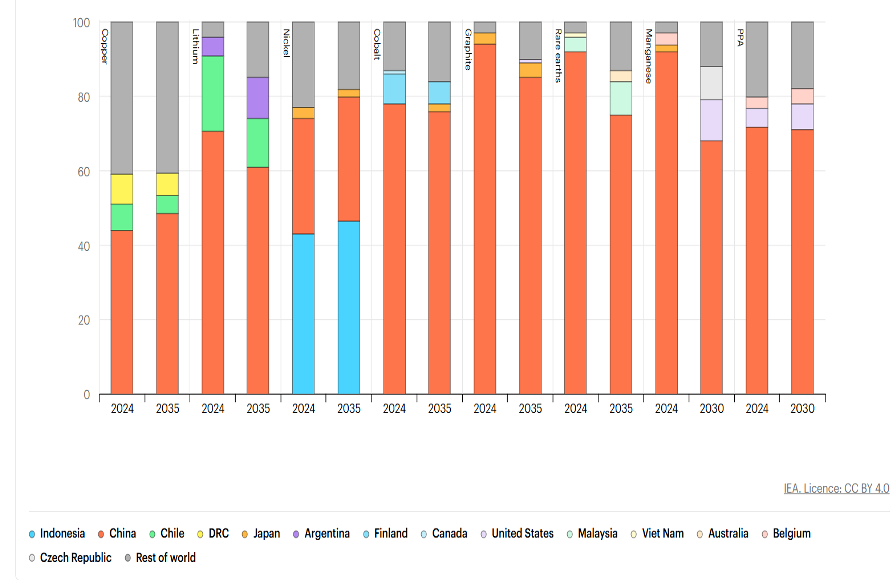

Three countries controlled 77% of the key energy transition raw minerals in 2024. Three countries controlled 86% of the refining capacity in 2024, with 90% of supply growth coming from Indonesia (for nickel) and China (for cobalt, graphite and rare earths). Given rising geopolitical tensions, the geographical concentration of mining and poses a severe risk to global supply chains.

93% of global lithium is mined in Australia, Chile, China and Argentina.

50% of global nickel is mined in Indonesia.

66% of global cobalt is mined in the DRC.

80% of global graphite is mined in China.

The geographical concentration of refining of key materials is no better – as the chart below shows.

And Chinese dominance of the market does not stop at mining and refining raw materials. The production of batteries themselves is also heavily dependent on China:

China produces 80% of global battery cells.

China supplies 85% of global cathode active materials.

China supplies over 90% of anode active materials.

China controls 80% of lithium hydroxide output.

Global Lithium Supply is Constrained.

But the real supply pinch point is Lithium - key to the continued growth of the EV sector – for which demand is projected to grow by 500% by 2040. Current lithium production is only just keeping pace with demand and the IEA projects that supply from existing and announced mining projects only meeting 60% of projected demand by 2035 – which is deeply problematic, given it takes around 16 years to develop a lithium mine.

Replacing the global stock of ICE vehicles with EVs will require 16-20 million tonnes of lithium – or 100 million tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE). Since estimates of total global lithium supply are around 22 million (105 million tonnes of LCE), it is clear that very little lithium will remain for other battery demands (data centres, mobile phones, electric tools etc). The outlook for cobalt and copper is similarly alarming, with existing mines and projects under construction estimated to meet only 50% of projected cobalt requirements and 80% of copper needs by 2035.

What does this mean for Electric Vehicles?

The EV market is growing fast. Over 17 million EVs were sold globally in 2024 - the difference between EV sales in 2024 and EV sales in 2023 was 3.5 million: greater than the total number of EVs sold in 2020. EVs account for around 90% of the world’s battery demand in 2024, with demand expected to triple by 2030. Since the most major component (and therefore cost) of an EV is its battery, the impact of raw material surpluses (and the projected future shortfall) is crucial for EV manufacturers and the high geographical concentration of mining and processing in their supply chain increases their exposure to geopolitical and market distortion risk.

Growing political risk is exacerbating these supply side risks. Governments increasingly identify rare earth elements (RRE) and minerals as strategic industries, crucial to national security and are devising strategies to protect their national interests. The rise of economic nationalism will do nothing to slow this phenomenon – as demonstrated by the way that access to raw materials became a flashpoint in the trade dispute between the US and China.

Conclusion

EV take-up is critical to the success of the energy transition. However, EVs face a combination of compounding risks which threaten their ability to play that role in the longer term.

High geographic concentrations of production and refining of raw materials will exacerbate the competition for natural resources which is the inevitable consequence of rising geopolitical tensions and economic nationalism. There are insufficient lithium mines in development to produce the necessary raw materials. African nations are (quite rightly) seeking to move up the value chain, which will create processing bottlenecks as facilities and training programmes are developed. least as access to critical raw materials becomes a national security issue. Hostile state actors are seeking to destabilise existing supply chains often using mis-and dis-information campaigns to ingratiate themselves with producer state governments in order to displace Western companies with their own.

This combination of geopolitical and supply chain factors which act together to compound the risks, as well as demand-side pressure for alternative zero-emission vehicles, suggest that the lifespan of EV market-dominance as the replacement for ICE vehicles may be limited. The wise investor may therefore draw the conclusion that it would be prudent to bet against EV dominance, on the basis that, by the middle of the next decade, hydrogen-powered cars will overtake EV as the dominant force in the ZEV market. If that is correct, those investors who have poured hundreds of millions of dollars of investment into bringing EVs to the market may find themselves brutally exposed by declining market share forced on the EV sector by geopolitical risk.

Companies in the mining and EV sectors would be well-advised to seek geopolitical counsel which can help them understand and navigate these ever-more complex and intertwined geopolitical, policy, technology, and market and demand risks. Being ready to act on that advice to adjust and modify (or diversify) their investment strategies accordingly will mean the difference between commercial success and failure.