Trump and the Geopolitics of Energy

At the beginning of this month, as US forces poured across the Venezuela border and dozens of Blackhawk helicopters buzzed low over Caracas, most people assumed that the objective was oil, not the liberation of the people of Venezuela. After all, as we had been repeatedly informed by the press, Venezuela has the world’s largest reserves of oil.

The following week, Iran was shaken by the largest protests ever. For a moment, the regime seemed about to fall. Then they got their guns out and started slaughtering their own people to hang onto power.

Immediately on the heels of Iran and Venezuela came Trump’s threats to Greenland (what a year 2026 has already been for geopolitics!). The world teetered on the edge of a confrontation between Europe and the US. The Western Alliance disintegrating before our eyes. I wrote about the Trump obsession with Greenland – access to large amounts of critical raw materials (25 out of the 35 minerals on the EU’s critical list are found in Greenland, with some estimates placing those reserves at between 10-20% of the world’s total) and control over the increasing sea access to the NW and NE Passages, which as the polar ice melts risks leading to an increased in Chinese and Russian influence in that region in the US’ front garden. That rationalisation seemed to make sense: why else would Trump risk the wrath of Europe and, if Greenland was likely to be independent in 10 years, then better it was under US than Russian or Chinese control, surely?

But what if the actual reason was oil?

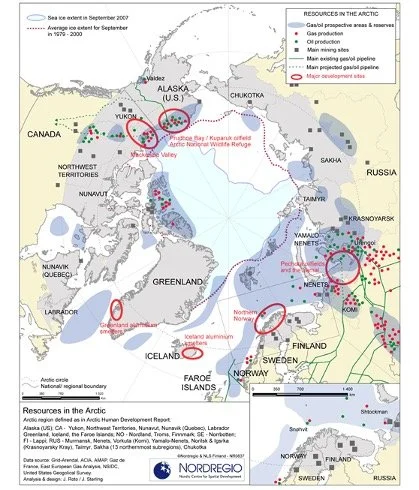

According to Nunaoil and MRA, there could be up to 29 billion barrels of oil on Greenland. Whilst a US Geological Survey report from last July places a lower estimate on oil reserves (around 8 billion barrels of oil), it focuses on W Greenland only and estimates the gas reserves at around 91 tcf. The same US Geological Survey also estimates that the Arctic Basin holds around 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources and around 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas resources. Greenland itself holds only around 2% of the world’s reserves, but crucially it occupies the geographical location which controls the space from which any future exploration of the Arctic Basin would be launched. The table at Annex 1 shows how much potential the Arctic offers when viewed from the perspective of estimated oil and gas reserves.

Seen through the lens of hydrocarbon reserves and access to them, Trump’s Greenland obsession perhaps begins to have a thin veneer of logic. If, as I argued in the blog cited above, the US NSS is actually entirely about countering the Chinese threat, then it makes sound strategic sense for the US to double-down on controlling the world’s hydrocarbon resources to try and choke off China’s economic advantage. If the Arctic is the future for hydrocarbon production, then controlling Greenland is vital – the graphic below shows how critical Greenland’s geographical location is to gaining (or controlling) access to those potential reserves.

As this Australian Strategic Policy Institute Paper makes clear, the US is now so far behind China on tech (and renewables) that it would be reasonable to conclude there is no commercial sense in trying to compete with them, so the US should seek its competitive advantage elsewhere. Since China still relies on hydrocarbons for between 85-90% of its energy mix, if the US can choke off the supply of cheap oil and gas to China, it may be able to slow Beijing’s headlong rush to tech supremacy and give itself a chance to get back into the race. Even if China is not the focus, or it proves too lengthy, costly or technologically difficult to access Arctic hydrocarbon reserves, there is still an argument that it makes strategic sense for the US to try and corner or control as much of the global hydrocarbon market as possible, given that there is no credible assessment which does not project hydrocarbons continuing to play a core role in the global energy system out to 2050 (depending on the scenario, the IEA projections show that hydrocarbons will meet between 20-60% of global energy demand by 2050).

What Does the NSS Say?

The focus on hydrocarbon dominance and a willingness to use energy policy as a tool of diplomatic and international commercial leverage is a dominating feature of the NSS. One of the NSS’ main goals for the US is ‘Energy Dominance’, which it defines as ‘Restoring American energy dominance (in oil, gas, coal, and nuclear) and reshoring the necessary key energy components is a top strategic priority’. It goes on to specifically state that expanding US ‘net energy exports will…curtail the influence of adversaries…and…enable us to project power’. At the same time, the NSS rubbishes renewable energy which ‘subsidises our adversaries’. In all ‘energy’ is mentioned 20 times in the Strategy in relation to every corner of the world. And when Trump says ‘energy’ he means hydrocarbons (with a bit of nuclear).

In terms of controlling global hydrocarbon supplies, it is illuminating that the first international trip of President Trump’s second term was to Saudi. The NSS, whilst downgrading the priority accorded to the Middle East because it is no longer ‘the world’s most important supplier of energy’, states that the US will no longer ‘hector these nations—especially the Gulf monarchies—into abandoning their traditions and historic forms of government’, indicating a much more relaxed approach to relations with the region and one which (according to the NSS) has ‘revitalised [US] alliances in the Gulf, with other Arab partners, and with Israel’. Seen through the prism of controlling access to the world’s hydrocarbon resources, this reads as if the Trump administration feels it has tied up the support of the region’s main producers.

But what’s this got to do with Greenland?

It was telling that Trump’s comment after his meeting with NATO Sec Gen Mark Rutte (still not quite clear why he was negotiating with Trump rather than the Danes or the Greenlanders, other than that he wins the prize for obsequiousness) referred to the ‘framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland and… the… Arctic Region” (my emphasis added). If the US can gain control of (or at least control the access to) the Arctic’s hydrocarbon reserves, it not only puts itself in a dominant position on the world markets, but, by controlling them, can influence both the global supply (and therefore the global price) as well as supply and price of sales to China. And, if actively exploiting the Arctic’s hydrocarbons proves too difficult, arduous or expensive, then preventing China from accessing them is almost as good.

If this is all about China, why reference Venezuela, Iran and geopolitical tensions with Europe?

The answer is that I am not sure that Trump’s hydrocarbon strategy will work. Whilst accepting that Iran and Venezuela (in particular) contribute comparatively little to the international hydrocarbon markets (see Annex 2 below for the top 10 global producers), it was noticeable that the oil price barely shifted in response to events in the two countries and the rising trans-Atlantic tensions – on 15 December Brent was $61.6/barrel; on 22 January it was $64.2/barrel - suggesting that at current production levels, the global market is over-supplied (and perhaps that geopolitical instability risk is now priced in). OPEC+ has recently unwound its production curbs betting that market share will make up for lost price. That bet does not seem to be paying off – especially with the US itself increasing production.

Taking a longer view, global energy demand increased by 2.2% between 2023-24 and is likely to have increased by a similar amount between 2024-25. But IEA figures show that the lion’s share of that increase has been met by renewables, not hydrocarbons - an assessment which is supported by the oil prices’ inverse response, dropping from an average of $96/barrel in 2023 to $75 in 2024 and $62 in 2025. Looking at China specifically, the figures make for arresting reading. The Chinese national energy demand has increased by 40% over the last decade. However, the share of supply meeting that additional demand over the same period has shifted from 75% hydrocarbons: 25% renewables in 2014 to 35:55 (with nuclear making up the remaining 10%) in 2024. So China may be in the process of escaping the chokehold of reliance on foreign energy imports.

Conclusion

If Trump really is betting the US house on cornering the global oil and gas market, then it begs the question about which country or region might next find itself in the crosshairs of his administration. The news which broke late last night that Trump has sent ‘an “armada” of US naval forces towards Iran, “just in case” he had to take action against Tehran’ (quoting from the FT) may indicate which oil-rich country may be next on the list.

However, I wonder whether the focus on hydrocarbons may be a bet on the wrong horse. Whilst an increase in US access to supplies may help the US economy domestically, including by perhaps bringing down gas prices at the pump and may also act as a constraint on China’s economic growth, there is a strong argument that Trump’s international ventures may be mis-directed.

With the Exxon CEO describing Venezuela as ‘uninvestable’ and Caracas only supplying around 1% of global oil supply (though most of that went to China) Venezuela, with its decrepit production facilities and heavy oil which requires specialised refineries, was an odd place to start.

If the threats to take over Greenland – from which he has now, in characteristic fashion, walked back – were targeted at accessing Arctic hydrocarbons, it is another odd decision. In a frontier region such as The Arctic, 15 years to get from exploration to production is a realistic timeframe. Even if exploration were viable and were to begin tomorrow, the dependence of the world (and particularly China) on oil and gas as the key energy input is likely to look very different by 2040.

Trump may feel that his newly solidified relations with the Middle East (and The Gulf in particular) have bought the loyalty of the Gulf countries. But his glad-handing of the regimes does not appear to have noticeably slowed Saudi production (which has increased by an average of just over one million b/d over the last year).

Intervention in Iran makes more sense - although Iran’s production lags way behind its potential, it is not in Venezuela’s ‘uninvestable’ category and currently supplies around 13% of China’s annual oil imports.

Even if his bet is correct, and the US begins to corner global hydrocarbon supplies, squeezing exports to China, pushing their prices up in the process and making Chinese products less competitive on global markets, the fact that increases in China’s energy demand are increasingly being met by renewables means that Trump’s gamble may already be too late. If it has not already done so, the Chinese economic horse is in the process of bolting the hydrocarbon stable.

Annex 1 – Top 10 Countries, Estimated Reserves

| Entity | Estimated Oil Reserves | Estimated Gas Reserves |

|---|---|---|

| Venezuela | 300+ billion bbl | 200+ tcf |

| Saudi Arabia | 260+ billion bbl | 300+ tcf |

| Iran | 155+ billion bbl | 1,000+ tcf |

| UAE | 100+ billion bbl | 210+ tcf |

| Iraq | 145+ billion bbl | 140+ tcf |

| Russia | 80+ billion bbl | 1,600+ tcf |

| United States | 40+ billion bbl | 600+ tcf |

| Arctic region (undiscovered) | 90 billion bbl | 1,669 tcf |

Annex 2- Top 10 Global Oil and Gas Producers

| Country | Oil Production | Gas Production |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 12+ mb/d | 100+ bcf/d |

| Russia | 10+ mb/d | 70+ bcf/d |

| Saudi Arabia | 10+ mb/d | 11.0 bcf/d |

| Canada | 5+ mb/d | 15+ bcf/d |

| China | 4+ mb/d | 20+ bcf/d |

| Iran | 3+ mb/d | 30+ bcf/d |

| Iraq | 4+ mb/d | 8+ bcf/d |

| UAE | 3+ mb/d | 10+ bcf/d |

| Brazil | 3+ mb/d | 5+ bcf/d |

| Norway | 2+ mb/d | 10+ bcf/d |